Why Your Innovation Team May Be Stifling Innovation, and Other Strategy Lessons From Peas

Innovation is great. I think so, I’m sure you think so, and I suspect we all think so. Innovation is good for business, and it’s good for us, and it’s healthy.

I like to think I’m kind of innovative; my job title is even “Innovation Leader”. I’ve written a mobile app to count fish using Watson, and I created the world’s first application server in a hat, and invented a cuddly throwable application server. (Remember, not all inventions change the world. Or are useful.)

Barriers to innovation

And yet … like many of us, I wish I innovated more. Why aren’t we all innovating as much as we would like? What’s holding us back? In every organisation I’ve worked with, the barriers to innovation are depressingly similar:

- Time

- Money

- Ideas

I’m not going to write about how to come up with better ideas, because there’s a lot of great material out there. Let’s talk instead about how to make more time. The answer is surprisingly simple. All you need is …

… a time machine.

Of course, a time machine only fixes half the problem. You’re also going to need office space (well, in 2021 maybe not so much). And you’ll likely need cloud compute, or some cool bits of hardware, or external expertise. The way to secure those resources is …

… a money tree.

What if you don’t have a time machine or a money tree? Well then, sadly, you’re in the same boat as the rest of us. The good news is that there are ways to make time to innovate without defying the laws of physics or economics.

Strategies for making time

Techniques for building innovation into an organisation range from a centralised innovation department to just … allowing slack in the system for grassroots innovation. There are lots of options in the middle, too, such as hackathons and 20%-time projects.

Before we discuss the tradeoffs of the various strategies, I’d like to share a story. If you went to an American school, you were most likely taught about George Washington Carver, who invented peanut butter. In fact, Carver’s contributions to the science of ‘not starving’ were much more significant - and he actually didn’t invent peanut butter.

Carver was born into slavery in the American South, just before the Civil War. As if that wasn’t a rough enough start to life, as a baby he and his mother were abducted by slave raiders. His master managed to recover him, but, sadly, not his mother. When slavery was abolished Carver was raised as a son by his former master. However, educational prospects in his area were limited, so Carver travelled across the country, working his way through school and then university as he did so. Carver had a knack for plants, so he studied botany and went on to teach it.

Even after the abolition of slavery, life was bleak for African Americans in the South. Cotton is an unusually needy crop, and generations of cotton farming had stripped all nutrients from the soil. The survivors of slavery were left to try and scratch out a living growing cotton on soil which could not support them - or anyone. The land, and the people, were exhausted and hungry. It was hard to see a way out from the vicious cycle of poverty; expensive fertilizers which might have restored the soil were far beyond the reach of farmers who could barely feed themselves.

If you’re a keen gardener, you probably know that peas and other legumes can fix nitrogen from the air and enrich the soil. Despite the name, peanuts are related to beans, and also improve the land.

This is where Carver comes in. He discovered that by rotating cotton crops with peanuts, farmers were able to grow more cotton. Farmers loved the improved cotton yields, but they had a problem. Peanuts. What should they do with all of these peanuts they were producing?

At the time, peanuts were barely considered a crop, and were only used for animal feed. While people were going hungry, peanuts were being discarded as waste. This is Carver’s second great contribution. Carver pointed out that peanuts were high in nutrients, especially high in protein, and that they were also pretty tasty. He catalogued peanut recipes and invented many more, such as chocolate-covered peanuts. Carver’s work led to the adoption of peanuts as an ingredient, which persists in Southern cooking to this day. He also invented some surprising industrial uses for peanuts, such as peanut shampoo and peanut nitroglycerine. (A century earlier, Antoine-Augustin Parmentier was responsible for a similar effort to change the image of the potato. Parmentier’s work led to the decriminalization of potatoes in France, which just goes to show the history of food is stranger than you might imagine.)

Carver was a prolific inventor, and his innovations improved many lives, but I think there’s a deeper lesson in his story. The way peanuts can enrich soil while also yielding a useful crop is profoundly counter-intuitive. It’s like subtracting one from one and ending up with four. Bonkers.

Do we see these sort of ‘should be subtractive but are additive’ effects anywhere else? I believe we see them in people. If you ask a team to do the same thing, over and over again, they get tired. They burn out. Productivity suffers.

Rest helps revive tired teams, but sometimes a change is as good as a rest. When a team is following its passion and innovating, they’re inspired. They get a bounce in their step; their eyes sparkle and they stay late just because.

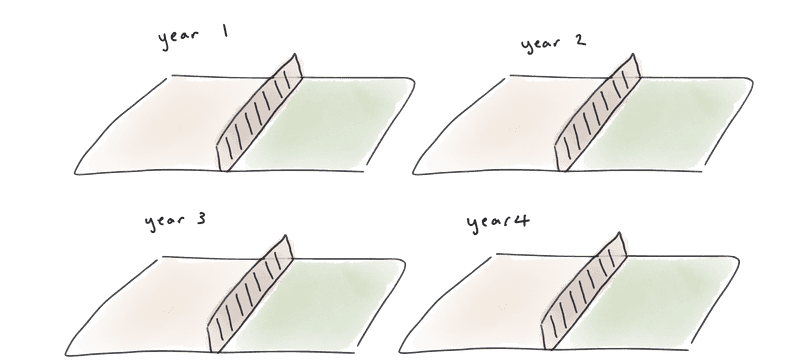

This is why setting up a dedicated innovation teams can sometimes miss out on the full potential of innovation activities. Siloed innovation teams are a bit like repeatedly growing cotton on one field, and repeatedly growing peanuts on a neighbouring field. The innovation team will be having fun, but they may miss out on the experience of real world challenges which would lead to more meaningful innovations. Meanwhile, the ‘business as usual’ team risk being ground down by too much work and too little play. Innovation, particularly Big Innovation, needs to be managed differently and funded differently, so innovation teams play an important part in an organisation’s innovation portfolio – but they shouldn’t be the only entry.

20% projects

Many businesses recognise the value of rotation to spread the innovation fun, and have adopted different strategies to support part-time passion projects. For example, Google famously has a 20% rule which allows employees to spend one day a week on projects of their choosing. Many Google flagship products, such as GMail, Google Maps, and Adsense, originated from this part-time employee tinkering.

There’s a problem, though. Often, takeup is low, and the program ends up being a headline, rather than a reality. This isn’t because of leadership malice; it’s just that there is always more work to do than there is time. Our day jobs expand to fill the contracted working hours, and then usually expand beyond them. We’re bogged down by day-jobness.

Hackathons

To counteract this, some organisations organise hackathons. The idea is that employees go somewhere, eat junk food, drink too many caffeinated beverages, stay up late, sleep on the floor, and build exciting prototypes. The problem is that hackathons almost always happen on the weekend. The time shortage is being ‘fixed’ by taking a chunk out of employee’s personal time.

More generally, employee ‘passion’ can be used as a means of extracting extra labour from the workforce, without extra compensation. Loving one’s job is good, but it shouldn’t be a lever to enable exploitation.

Off-plan post-release weeks

“Off-plan post-release weeks” are one of my favourite innovation mechanisms. The name isn’t great, because I made it up. The origin is an experience I had in the WebSphere product team, many years ago. Back when we only released infrequently, releases were a big big deal. There was always a bit of a rush to meet the release deadline and get as many features as possible onto the train before it left. Here, ‘bit of a rush’ is a nice way of saying ‘increasingly stressful period of evening and weekend-working’ (this is a great reason to make releases more frequent, but that’s a separate topic).

Once the release was out the door, there’d be a collective flop and let down of adrenaline among the development team. To make up for desperate weekend-working grinds, we’d get all time off. (Have I mentioned that more frequent releases are a great idea with many efficiency benefits?) If the release had just been mildly exhausting, we’d get a different kind of treat. All plans and schedules and backlogs would be shelved for a sprint, and the team could work on whatever product features they liked.

It sounds like a rough deal that we after working really hard our reward was … the opportunity to do work. But it was great! The team loved it, and some of our best features came out of those off-plan weeks. What makes this model stickier than 20% time is that the whole team took it at the same time. Day-to-day commitments couldn’t derail the innovation work, because they all went away.

The success of “free time to do work” as a reward shows the importance of autonomy; allowing teams to decide what to build, even for just a sprint, made people happy and unleashed a flood of innovation.

Slack in the system

What if innovation could happen without any 20% rules, or post-deadline-exhaustion, or junk food and Coca-cola? What if we just … had enough space to come up with great ideas, and then had enough time to try them out?

Well, it’s a bit utopian. Most of our workplaces aren’t so luxurious. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strive for space. There’s a growing body of evidence that healthy workspaces, with generative cultures and happy employees, are associated with higher business performance. An over-emphasis on productivity metrics, like other metrics, could actually be lowering productivity. Even five day weeks might be lowering productivity.

What does this mean in practice? As leaders, we need to re-evaluate how reliant we are on superficial productivity metrics, and shift to thinking about outcomes instead. What might look like a spontaneous employee ball-game involving maltesers, comedy hats, and wastepaper baskets, could actually be an employee wellness experience which is getting blood circulation going, improving employee health, and averting (expensive) staff burnout. What might look like goofing off or daydreaming could actually be laying the foundations for a breathrough innovation.

In the next part of this blog, I’ll talk about choosing innovation winners, innovation funnels and innovation fizzles and the perils of MVPs.