The necessary death of software systems

Sometimes, death is a feature, not a defect

It’s Hallowe’en! Let’s talk about mortality, death gods, and zombies.

I know, I know, you studied computer science instead of biology precisely so you didn’t have to deal with dead things. Most of us who work with software spend a lot of effort trying to keep our applications alive. If you’re an SRE, keeping systems alive is basically your whole job description.

Ryuk and the god of death

But you know what? Death is a necessary fact of life, especially in the land of bits and bytes. I realised this when I was trying to sort out some compatibility issues between Quarkus, Podman, and Testcontainers. In order to get Quarkus Dev Services (which use Testcontainers under the covers) to work with Podman on my Mac, I had to adjust my environment variables to disable something called Ryuk:

export TESTCONTAINERS_RYUK_DISABLED=true # this is a bad ideaWith this, everything more or less worked … but it turned out it wasn’t the right way to solve my problem. Why? What was Ryuk, anyway? This comes back to the question about what Testcontainers is doing, or ‘why would I useTestcontainers rather than just starting containers directly?’ (If you’re using Quarkus, the answer is that you actually don’t use Testcontainers directly, Quarkus uses Testcontainers for you to transparently start all your dependencies before you or your tests need them. But let’s not worry about that for now.)

Testcontainers does two really useful things; it has libraries in all the popular languages to interact with a container runtime. That means instead of having to fuss with Runtime.exec or exec.Run, you can just call a nice API to start your container. But the other useful thing Testcontainers does is stop your containers. No more discovering a container still hogging your RAM days after you last used it, just because you forgot to shut it down.

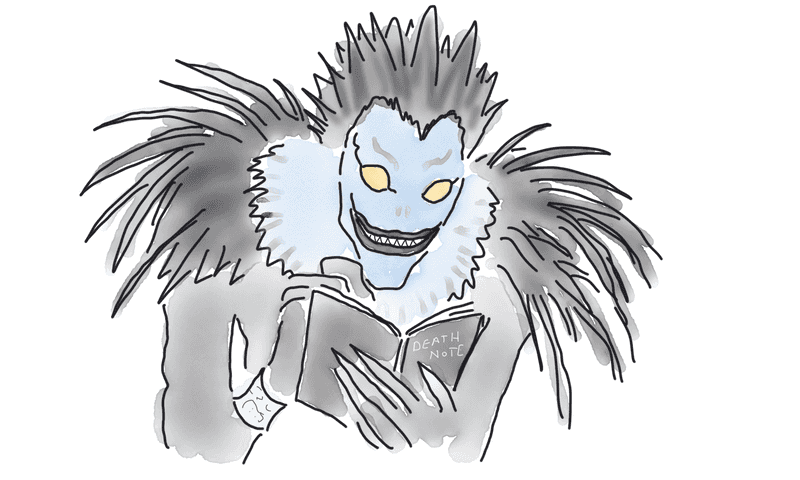

How does Testcontainers shut down abandoned containers? This is where Ryuk comes in. The Ryuk service is a specialised container whose job is to clean up other containers. That is, it’s a container-killer. A helpful, appreciated, container-killer. And the name? Ryuk is named after Ryuk in the Death Note manga series. Ryuk is a shinigami, or death god. Although Death Note’s Ryuk is capricious and self-interested, in Japanese folk culture shinigami are often presented as helpers that lead people towards the world of the dead, a bit like a friendlier version of the grim reaper.

So Ryuk definitely isn’t something we want to disable. It’s garbage collection at the process level. No one wants stray containers living forever. The right way to configure Testcontainers for Podman, on Mac, is to edit ~/.testcontainers.properties and add the following line:

ryuk.container.privileged=trueWhat’s this doing? It’s making Ryuk, the death god, a bit more god-like. You will also need to run Podman in rootful mode, so that it has privileges to pass on to Ryuk:

podman machine set --rootfulDo we have evidence how useful stopping things actually is? We do.

The zombie menace

If a Testcontainers container doesn’t stop, it’s a minor irritation. It might consume a little bit of CPU and memory until your laptop is next rebooted, or in the worst cases, it might cause interference and weird results in subsequent test runs. But when “not stopping things” is multiplied across an entire industry, the consequences can be serious.

The Anthesis institute have done a series of studies to work out how widespread zombie servers are. They found that 25-30% of servers are “comatose” – that is, they haven’t done any useful work for six months. Here, “useful work” doesn’t mean “they weren’t just serving cat videos,” it means they haven’t delivered any information or computing services for six months or more. That’s a shockingly low bar, and yet 25% of systems still didn’t meet it.

What if we raise the bar slightly and look at servers where the utilisation was under 5% (which is still a pretty atrociously low bar)? These ‘under-utilised’ servers made up another 29% of the pool. If you combine the totally-comatose and mostly-comatose servers, that makes up two thirds of the servers.

Even systems that are in regular use are often only used for part of the time. In 2021, $26.9 billion was wasted on always-on cloud instances.

In other words, we’re paying for hardware, and electricity, for systems that do … nothing. Sustainable, it is not. What our industry needs is a nice friendly shinigami to take down these systems.

We’re starting to see shinigami which can shut systems down out of hours. For example, the DailyClean tool provides a friendly interface for scheduling ‘alive times’ for Kubernetes workloads.

Randomised rebirth

However, zombie-destruction is a harder problem to solve. If something is never being used, why did no one just turn it off? Often, these systems have been lost out of institutional memory, because a process changed and the old process was never properly retired, or a team was disbanded or a project stopped. Forgotten systems are, by definition, invisible.

Sometimes, people know the system is useless, but it’s too much trouble to shut the systems down. This is a particular problem in regulated industries, which are (understandably) averse to casually shutting down parts of their infrastructure. I heard a story of an outsourcing provider that shut down what they thought was an unused server. Shortly after, the phone rang with a very very angry client on the other end. The ‘unused system’ turned out to be the backbone of the client’s network infrastructure, just mislabelled. Avoiding this kind of awkward scenario is why some companies enforce heavy bureaucracy before letting any of their employees go anywhere near a power switch. In these organisations, the paperwork to prove a system is unused can take many months.

There is a better way. I mentioned that SRE is the business of keeping systems alive. One of the tools SREs use to do this is regularly killing systems. What? Really. Damaging infrastructure creates resiliency, and killing infrastructure creates immortality. It’s a bonkers paradox, but it works. Chaos engineering is the practice of arbitrarily shutting down parts of a system to exercise recovery processes. This is known as deploying chaos monkeys. In the ideal case, the system copes with the loss of a member by failing over or routing around the casualty. In the bad case, there is learning!

We can extend this to zombie-hunting. One way of detecting zombies is known as a “scream test” (very Halloween-y!). The system gets shut down, and then the team wait for screams. If there were none, it wasn’t being used. This methodology can be formalised as an eco-monkey. As long as everyone is confident a system can be brought back up (‘LightSwitchOps’), it can be subjected to a test-shut-down with relatively low risk. If that sounds a bit too scream-y for comfort, AIOps can identify under-utilised systems by monitoring traffic and hardware load levels.

Killing systems is important. It’s important to extend their life, paradoxically. It’s important to save resources, and save the planet. And it’s important so that our laptops don’t grind to a halt under the weight of two dozen unused databases. So this Halloween, let’s give some thanks to our techno-shinigami, and see if we can write some more.

I’m grateful to Ixchel Ruiz for telling me about the origin of the Ryuk name, and for the conversation that inspired this blog.